[ad_1]

Under cover of darkness in 1890, two headhunters climbed over a gate and crept into a graveyard on Inishbofin, a remote County Galway island on Ireland’s Atlantic coast. In the ruins of a medieval monastery they found dozens of skulls. They selected 13.

“When the coast was clear we put our spoils in the sack and cautiously made our way back to the road,” Alfred Haddon later wrote in his diary. He and his accomplice, Andrew Dixon, smuggled the skulls on to a boat and sailed away.

For 132 years, the loot has sat in the anatomy department of Trinity College Dublin – specimens in the name of science and a theory, long-discredited, that the islanders were Ireland’s aborigines.

For the people of Inishbofin the skulls’ removal was a colonial-era violation that still stings, two centuries later. “They’re our ancestors, they should be allowed to rest in peace. They deserve respect,” said Marie Coyne, a local historian who has campaigned for the skulls’ return.

“The skulls were stolen, and there is an accomplice that’s keeping them stolen,” said Coyne. “I don’t see Trinity coming out of this well if they don’t give them back.” She has collected signatures from almost all of the island’s 170 inhabitants demanding the skulls’ return.

The campaign may be on the verge of success. On 14 December, the board of Trinity College is to consider returning the remains to Inishbofin – a decision that could set a precedent for other human remains and artefacts held by the university.

The board’s decision will test a new formal process to review the university’s historical legacy since the institution’s foundation in 1592 – a legacy that includes tomb-raiding, slavery and racism. The next issue, to be considered in January, is whether to rename a library named after George Berkeley, an 18th-century philosopher who owned slaves.

“The methodology hopefully will work for other issues,” said Eoin O’Sullivan, a professor and senior dean who is heading Trinity’s legacies review working group. Statues, portraits, collections and the names of lecture halls and academic prizes may come under scrutiny, he said. “I’d be surprised if not. We’ve been here 430 years.”

The fate of the skulls is part of a global reckoning that is pressuring institutions to return human remains obtained under academic guise, said Pegi Vail, a New York University anthropologist and curator. Trinity’s decision will resonate beyond Ireland, she said. “It will have weight. The more institutions that join the wave of individuals wanting to do the right thing, the better. They can set a precedent.”

Vail is part of the Inishbofin campaign. Her ancestors came from the island; her great-great grandfather was among those who had their heads measured by visiting researchers in 1892, two years after the monastery skulls had been removed. “The theft was incredibly egregious,” said Vale. “Each skull, each fragment represents a person.” Vail is making a documentary about the subject.

In the late 19th century there was a belief that craniology – the study of skulls – could shed light on the intelligence and development of different races. Ireland’s west coast islanders were of special interest because of a theory that they descended from an indigenous race undiluted by Anglo-Saxons and other outsiders.

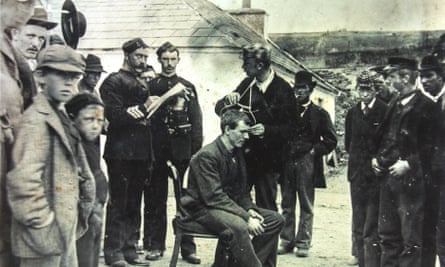

Haddon, a British anthropologist and ethnologist, and Dixon, an Irish medical student, sailed to Inishbofin in 1890 ostensibly as part of a fishing survey. In his diary Haddon described their clandestine mission to the ruins of St Colman’s monastery in derring-do tones. The pair told their boat’s crew that the sack of centuries-old skulls contained poitín, an Irish moonshine.

They eventually delivered 20 skulls to Trinity – 13 from Inishbofin and the rest from the Aran Islands and St Finian’s Bay in County Kerry, according to Ciarán Walsh, an independent scholar and curator who has studied the “Haddon & Dixon collection” at the university’s Old Anatomy Museum.

The Inishbofin skulls were of ordinary parishioners that had been kept at the monastery for safekeeping, a common practice at the time, said Walsh, who is part of the campaign for Trinity to return the skulls. “This collection is so unethical they can never display it in public.”

Trinity’s provost, Linda Doyle, said dealing with the university’s past would be a learning process driven by evidence-based submissions. “The goal is to shed light, not heat, on these complex legacy issues.”

Coyne, who runs Inishbofin’s heritage museum, thinks the debate merits heat. “I’d personally light a bonfire just to get this blazing so they would feel there is nowhere else for them to go but to return the skulls.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Meet Our Successful Graduates: Learn how our courses have propelled graduates into rewarding

careers. Explore their success stories here!

Discover More About Your Future: Interested in advancing your teaching career? Explore our

IPGCE, MA, and QTS courses today!

Explore Our Courses: Ready to take the next

step in your education journey? View our

comprehensive course offerings now!