[ad_1]

The CEO and executive chair of U.S. News & World Report delivered an impassioned defense of the magazine’s rankings last week, arguing the prominent colleges snubbing them “don’t want to be held accountable by an independent third party.”

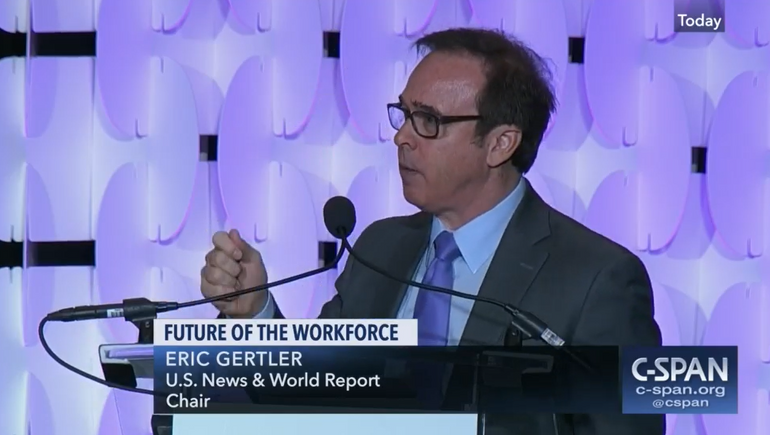

Eric Gertler’s missive in The Wall Street Journal escalates a three-month feud over the rankings as dozens of law and medical schools have withdrawn, accusing U.S. News of valuing prestige ahead of academic quality. The U.S. education secretary also recently took a stand against the rankings, prompting the publication to go on the defensive.

Gertler wrote in the Journal last week that U.S. News’ rankings represent one of the few sources where students can find “accurate, comprehensive information” on colleges.

The rankings do not capture colleges’ every nuance, he wrote, and comparing institutions across common data sets can prove challenging. But he rejected criticism that the rankings contribute to a decline in campus diversity or opaqueness in college admissions, as some opponents have suggested.

Gertler instead insinuated some law school deans are seeking to sidestep the fallout of an expected ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that would restrict race-conscious admissions “by reducing their emphasis on test scores and grades — criteria used in our rankings.”

“By refusing to participate, elite schools are opting out of an important discussion about what constitutes the best education for students, while implying that excellence and important goals like diversity are mutually exclusive,” Gertler wrote.

Gertler’s essay constitutes one of the magazine’s most comprehensive responses to the rankings boycott since the groundswell began in November.

Yale and Harvard universities’ law schools were the first to pull out of the rankings that month, saying the system penalizes institutions that want to prioritize placing students in public service careers. Waves of other law schools followed, citing similar reasoning, and now most programs in the top 15 spots of U.S. News’ list aren’t participating.

Harvard’s medical school became the first in that discipline to turn away from the rankings in January, spurring rounds of other medical schools to do the same.

U.S. News has said it will still rank law schools using publicly available information the American Bar Association provides. It also rewrote the formula used to rank the law schools, making it rely less on a survey that academics, lawyers and judges complete about their perceptions of institutions. No law school has said the tweaks will cause them to return to the rankings.

More recently, two institutions — Rhode Island School of Design and Colorado College — rejected U.S. News’ Best Colleges undergraduate rankings, the publication’s bread-and-butter product. Both colleges said the rankings reinforce inequities.

The mounting movement against the rankings has prompted speculation whether colleges will abandon them altogether.

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona essentially called for this at a conference Harvard and Yale law schools organized this month. He said at the event that institutions should “stop worshiping at the false altar of U.S. News and World Report.”

Rankings disincentivize the wealthiest institutions from enrolling and graduating more underserved students, Cardona said at the event. That’s because doing so harms their selectivity, a factor in U.S. News’ formula.

Cardona said colleges,“not some for-profit magazine,” should set the higher education agenda.

“Tell them to admit more students of color, admit more Pell Grant recipients,” Cardona said. “Admit them. Enroll them. Support them. And propel them to graduation day and rewarding careers.”

U.S. News immediately issued a response to Cardona, writing in an open letter he should direct colleges to be more transparent with their data. The magazine noted a particular dearth of public information related to graduate schools.

More openness from colleges would allow prospective students and their families to “make meaningful comparisons between institutions, based on factors such as financial information, admissions data, and outcome statistics,” U.S. News wrote.

The magazine first published its rankings in 1983. Colleges and critics have since come down on U.S. News for certain pieces of its methodology, such as use of the reputational survey and applicants’ SAT and ACT scores.

These factors are too easily gamed, opponents argue, like in 2008 when Baylor University dangled financial incentives for first-year students to retake the SAT and ACT, potentially bolstering their test scores, and in turn, Baylor’s rankings placement. The university ended the practice shortly thereafter.

Other events last year corroded the rankings’ legitimacy. A Columbia University mathematics professor uncovered evidence the Ivy League institution sent incorrect data for the rankings, leading the university to investigate. Though Columbia said it would not participate in the 2023 rankings, U.S. News listed it regardless.

And last March, a former business dean at Temple University was sentenced to 14 months in prison and fined $250,000 for giving U.S. News false data.

[ad_2]

Source link

Meet Our Successful Graduates: Learn how our courses have propelled graduates into rewarding

careers. Explore their success stories here!

Discover More About Your Future: Interested in advancing your teaching career? Explore our

IPGCE, MA, and QTS courses today!

Explore Our Courses: Ready to take the next

step in your education journey? View our

comprehensive course offerings now!