[ad_1]

Before the pandemic, Rose Hill Elementary in the Adams 14 district had four years in a row of low ratings. That changed this fall when Rose Hill students showed improvement on state tests — the only Adams 14 elementary school to do so.

The changes came from consistent leadership and an experienced team of teachers working hard to improve how they serve English learners.

“We haven’t had the massive numbers of people just leaving Rose Hill,” said principal Luis Camas. “This is my Year Five, and most of my teachers are still here. It’s making a difference.”

Adams 14 leaders are now sharing plans for how they hope to support more schools in making progress like Rose Hill despite years of low performance and failed state intervention.

They also insist their students are doing much better than dismal state test scores suggest, and they continue to fight outside intervention in the courts.

The district’s plans include making sure principals have the time and skills to work with teachers on instruction, developing a community school at Central Elementary that will provide services to the entire family, building career academies at Adams City High School, and providing more resources to the English learners who make up half the student body.

Some of these plans are new — like the community school — while others were proposed or tried before, but with limited follow-through. District leaders say this time is different because they’re working with the community and developing a comprehensive strategy, not just a “to-do list” of new programs.

Board member Maria Zubia said this time she’s seeing real steps toward change and believes the plans will outlast the current administration, so the work doesn’t have to restart next time there’s a change.

“That’s what’s exciting to us,” Zubia said. “There’s just things we see. I’m tired of people who talk, talk, talk, and there’s no action. I’m one of the realists; I need to see it.”

Some community members and experts are still skeptical. Nicholas Martinez, who leads the local advocacy group Transform Education Now, said leaders have not clearly explained to the community what’s happening or why.

“From my vantage point not a lot has changed,” Martinez said. “State data was released, and there’s not a ton of outliers. There’s not a ton of folks that said, ‘There’s a bright spot.’ I would love to know what has been the strategy for the district.”

How Adams 14 got here

Eight months ago, the State Board of Education ordered the reorganization of the Adams 14 school district — the most drastic step available under state law. The district has struggled with low test scores for more than a decade. Reorganization could lead to school closures or losing control of parts of Adams 14 to neighboring districts, but the plan will be led by Adams 14 community members and people from neighboring districts who support the district.

A few months prior to the state order, at the request of Superintendent Karla Loria, the school board had terminated its contract with the outside consulting firm that had run the district under state orders since 2019. State Board members were concerned Loria didn’t have enough details for a plan with a new management partner and that she wasn’t willing to give up enough control.

The district has spent much of its time and effort fighting the state’s orders. A reorganization committee has met just once, and the group is now looking for a facilitator.

Meanwhile, Loria has built a new leadership team largely made up of people she knows from past jobs. They’re turnaround experts, she says, from districts with experience serving students like those in Adams 14. Of the leadership team she inherited, Loria said she fired just one out of about eight people who have left. She said she simply made her high expectations clear and let people decide whether to stay.

The district now has a three-year, $5 million contract with national nonprofit TNTP, a consulting group that has traditionally focused on teacher evaluation systems, among other projects, to help with this work. Officials with TNTP did not respond to an interview request but released a joint statement with district officials outlining their work and the start of a strategic planning process.

After having lost state accreditation briefly twice in the last year, the district has also applied for an alternative accreditation from Cognia, an outside agency. Loria said she hopes it will give the community a sense of pride if they can say their district is nationally accredited. The process will also help the district get feedback from an external group about what is working and what’s not.

Still, many in the community wonder what the district is doing to improve student outcomes.

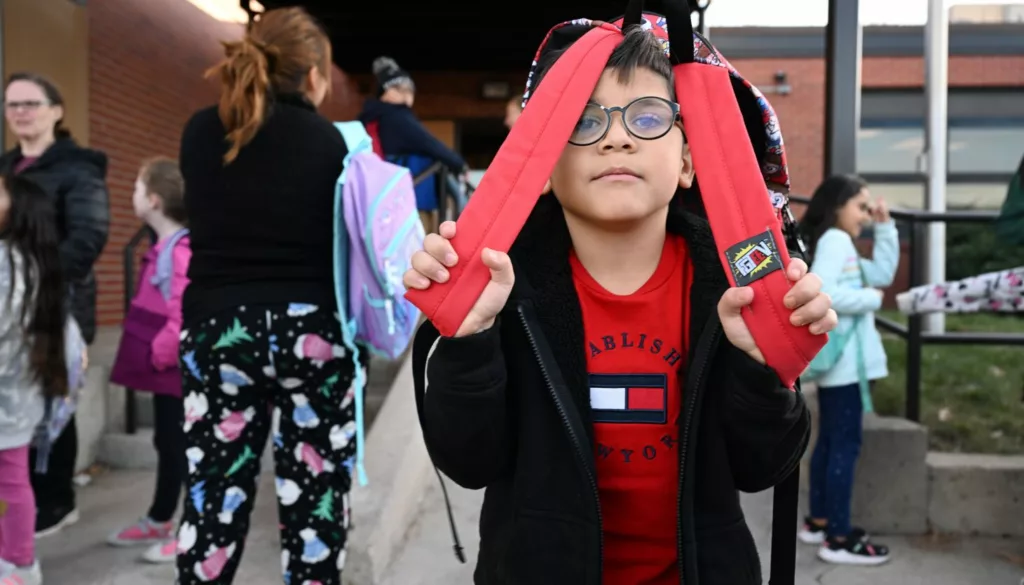

Teachers at Rose Hill credit consistent leadership and more support for English learners for the gains students have made.

Helen H. Richardson / The Denver Post

Over time, English learners have gotten more support

Adams 14 serves a little more than 6,000 students north of Denver, and about half of them are classified as English learners, or linguistically gifted, as the district now calls them. A federal complaint and investigation launched in 2010 eventually led to a finding that the district was violating the civil rights of those students and discriminating against their families, and has been under federal orders to improve.

Under the guidance of MGT, the previous state-ordered management company, the district finally completed a plan in 2020 for how to serve its English learners that met federal approval.

Since then, the district has been working on rolling out that plan, including dual language programming. Under Superintendent Loria, the district has brought in teachers from out of the country to provide students with more bilingual teachers.

“I see a great strength in supporting the dual language programming that will support not only students learning a second language but also strengthening their first,” Loria said. “We’re seeing progress there, but I think we have room to improve.”

This year the district added dedicated English language development teachers to each elementary school.

Raven-Syamone Wattley, a Rose Hill elementary teacher, said it’s made a big difference on top of previous efforts.

Wattley estimates about half the teachers at her school have a master’s degree in culturally and linguistically diverse education or English learner endorsements on their teachers’ license, with help from the district. She already has an endorsement and expects to finish her master’s this summer.

The district had also started providing a coach who helped her learn how to design lessons for English learners. But teachers at Rose Hill still had to split up their classes and shuffle students based on their English proficiency levels when it was time for English language development instruction.

That meant she got extra students whose needs she had to learn in addition to her regular classes.

Now, having a dedicated English language development teacher means she can focus on her students and how to incorporate English language development work throughout the rest of the day.

“It has made a huge difference for planning. That’s one less subject we have to plan for,” Wattley said. “English language development has improved drastically.”

Even as district leaders work to improve instruction for bilingual students, they believe the state system judges them unfairly because many students aren’t yet proficient in English. When first and second graders took the widely used STAR early literacy assessment this year, almost 60% of students who took it in Spanish met benchmarks, compared with just 23.5% of students who met benchmarks in English.

Rose Hill Principal Luis Camas, center, makes sure kids get in their parents’ cars after school. His five years at the school have helped provide consistency and academic growth.

Helen H. Richardson / The Denver Post

The district is focusing on principal leadership

Before the pandemic, Rose Hill faced the possibility of targeted state intervention if it were to receive one more bad rating.

But this fall, Rose Hill’s state rating went up to Improvement, the second highest level. The improvement needs to stick next year for the school to avoid state intervention.

Camas said his time at the school has allowed him to develop a culture and systems where teachers know how to look at data and talk about lesson planning. He is also one of seven Adams 14 principals who have gone through a University of Virginia leadership training program.

Loria said she’s made it a priority to have district staff support principals so they can focus, like Camas, on leading their teacher’s instructional work instead of having heavy administrative loads or long meetings about non-instructional tasks of running schools.

Staff retention is another priority in a district that has struggled with high turnover. District officials said in September that they’re on track to meet a goal of retaining 80% of high-performing teachers and administrators, but they did not provide Chalkbeat with current data.

At Rose Hill, Camas has added a new planning period for teachers so they each have two per day. Although he wanted to give overworked teachers a break from additional duties, teachers came to him and asked to start an after-school tutoring program.

Teachers at Rose Hill also lead other after-school programs, including a step club, archery club, and speed stacking. Those things help students want to come to class, and maintain good enough grades to participate, Wattley said.

Students at Rose Hill have access to after-school programs including a speed cup stacking club.

Helen H. Richardson / The Denver Post

Career paths at Adams City are in the works

Adams City High School is the district’s only comprehensive high school. It has received low state ratings since 2010 and has its own improvement plan.

For more than a decade — ever since the school moved into its new building off Quebec Parkway — district leaders have talked about plans to create more structured career pathways, or academies, in addition to the career classes the school already offers.

Many parents want these programs, and educators think they would motivate students and open doors after graduation.

MGT, the previous outside manager, was working to expand apprenticeships, certifications, and opportunities for college credit. The group said in 2019 that less than a quarter of the school’s students were participating in one of the school’s five career pathways, and data showed those students were more likely to graduate.

But Superintendent Loria said those plans weren’t substantial enough to lead to lasting improvement or aligned with other programs. Mostly, she said, they were documents with “just a list of things to do.”

This time, with the academies model, the district is working on integrating projects that tie to the career focus of each academy throughout the day in math, reading, and other classes. Loria has enlisted the help of nonprofit Connect Ed with a contract for $411,300 to help develop a more rigorous plan at the high school.

So far, the group has surveyed students to identify the four career areas that will become academies. The four academies are: health sciences and human services; architecture, construction, engineering and design; business, hospitality and tourism; and digital information and technology. Students in ninth grade next year will explore all four in their first semester, then commit to one academy for the rest of their high school experience.

District leaders say they aren’t worried about losing students to other districts if they don’t feel like they fit in any of the four pathways.

“Regardless if that’s going to be their career or not, they’re prepared for the workforce,” said Ron Hruby, the district’s director of career and technical education. “Our students are going to be able to do part time jobs as phlebotomists — think about the amount of extra money they would have.”

A $900,000 state grant will pay for some of the high school changes.

Career pathways have been part of the vision for Adams City High School since it opened.

Michael Ciaglo / Special to the Denver Post

Community school is key part of district effort

Central Elementary is the other Adams 14 school with its own improvement plan after receiving low ratings since 2012. The school is set to become the district’s first community school — a model that tries to address outside factors that affect learning.

The district has created a full-time coordinator position and enlisted the help of several partners. The State Board has signed off on the plan.

The coordinator is working with the school to survey the needs and identify services that can be offered to families. Such services could include a food bank, a clinic, or job help for parents. It’s a model some would like to see expand beyond Central Elementary. More than 71% of Adams 14 students qualify for free- or reduced-price lunches, a measure of poverty, and many families have health issues which they believe are tied to environmental factors.

The district has also worked on giving Central Elementary some additional flexibility. In recruitment, for instance, the district has created special incentives for people who want to work specifically at Central.

Jason Malmberg, the president of the district’s teachers union, says he feels this is the biggest difference in district improvement plans this time.

“The district has put their money where their mouth is,” Malmberg said. “This is just like everything else — you can’t just buy a label and slap it on the building. The idea is you’re responding to the barriers of education specific to that community. There is context that matters in children’s lives. And that’s not just coming from teachers or families anymore. That’s top to bottom, a culture shift in values.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at [email protected].

[ad_2]

Source link

Meet Our Successful Graduates: Learn how our courses have propelled graduates into rewarding

careers. Explore their success stories here!

Discover More About Your Future: Interested in advancing your teaching career? Explore our

IPGCE, MA, and QTS courses today!

Explore Our Courses: Ready to take the next

step in your education journey? View our

comprehensive course offerings now!