[ad_1]

When Andrew Avila landed his first teaching job at Chicago’s Bronzeville Classical Elementary in 2021, he got to work creating lesson plans for his students, who would be returning to in-person learning amid the pandemic.

The newly minted science teacher had access to Skyline, a new online curriculum created by Chicago Public Schools. It offered a wealth of materials and ideas connecting science to his students’ experiences. A lesson on thermal energy, for example, explained how air conditioner units increase summertime temperatures in Chicago.

Chicago teacher Andrew Avila, who uses Skyline at Bronzeville Classical Elementary, has occasionally felt overwhelmed by the volume of resources on the platform.

But at times, Avila felt overwhelmed by the sheer number of lessons and other materials, housed on a digital platform that could be tough to navigate.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m drinking water from a firehose because there are so many resources I can turn to,” Avila said.

CPS is betting big that Skyline — the unprecedented $135 million trove of lessons in math, reading, science, social studies, and other subjects — will help students bounce back from COVID’s profound academic damage.

The curriculum remains voluntary for schools, but the district has started pressing campuses that have not yet adopted Skyline to prove they have other quality curriculums in place.

An analysis by Chalkbeat and WBEZ found that roughly half of the district’s campuses report using Skyline for at least two subjects, with the highest adoption rates at schools that serve predominantly low-income Black students. In other words, Skyline is shaping the learning of tens of thousands of students, including some of Chicago’s most vulnerable, amid a high-stakes pandemic recovery.

District leaders say that by ensuring students get lessons that reflect their grade levels, Skyline helps teachers speed up learning rather than constantly backtracking to material students should have learned earlier. Some educators praise Skyline for offering rich resources that help novice educators such as Avila hit the ground running and seasoned ones rejuvenate their teaching.

But others say the curriculum is not ready for prime time. A wonky digital platform can make it hard for teachers to navigate a slew of lessons and assignments that many say can be overwhelming. In some subjects, student materials include dense blocks of text with few visuals that can especially challenge struggling learners.

The district says it is continually strengthening the curriculum — created in-house with help from several curriculum companies — with input from educators and students, including recent improvements to the online platform. Still, some educators remain wary of a centralized curriculum in a district that has traditionally given teachers leeway to design their own lessons.

Getting the Skyline rollout right is enormously important, say curriculum experts such as David Steiner at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Education. He notes that many teachers are routinely pulling materials off the web, acting “like DJs for playlists of instructional materials” — a task that’s unfair to lay on overworked educators and one that leaves students’ education to chance.

“In this moment of fragility and uncertainty, we need to reduce the zone of ‘anything goes’ and chaos, and, ‘This is my unique curriculum and my unique classroom,’” he said.

How a uniquely Chicago curriculum originated

In Chicago, wealthier schools have often been able to buy quality learning resources while low-income campuses made do with cobbled-together or outdated materials and books.

Former Chicago schools chief Janice Jackson saw a solution: a curriculum bank filled with high-quality lessons in every subject. She said it could tackle massive disparities in academic achievement across the city’s 500-some district-run campuses. What’s more, by developing it in-house, experts could tie in Chicago’s history and present day, making it more engaging for students.

The district enlisted five companies to help develop and implement the lessons and built-in assessments, with input from some Chicago teachers. It came to draw heavily on federal COVID-19 relief dollars to foot the six-year, $135 million bill. Ultimately, Skyline — and the technology it relies on — became some of the priciest items the district bought from outside vendors with pandemic recovery dollars.

Chicago formally launched Skyline in the summer of 2021, a couple of weeks before Jackson stepped down.

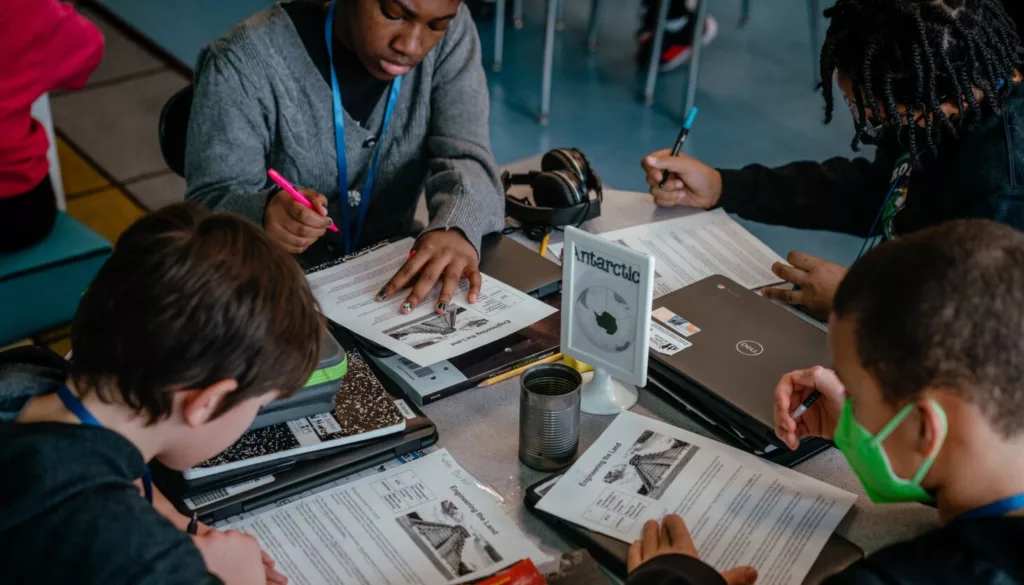

Javee Hernandez teaches her sixth grade students social studies using the new Skyline curriculum at Bronzeville Classical Elementary School.

That summer, Javee Hernandez — a veteran social studies teacher at Bronzeville Classical whose classroom is across the hall from Avila’s — joined principal Nicole Spicer and other school leaders in deciding whether to adopt the new curriculum. Bronzeville Classical, a test-in school on the South Side where students learn a grade ahead of their age, had opened just a few years earlier, in 2018.

The administration felt the school’s math and reading coursework was strong, but social studies and science could benefit from a revamp. Enter Skyline.

“This was a free, high-quality, rigorous option,” said Spicer. “Skyline became a resource that really was a no-brainer for us.”

The district has offered schools like Bronzeville a slew of incentives to opt into Skyline: free books and math supplies, dollars to spend on science lab equipment, expanded access to technology. But even as Bronzeville has embraced Skyline, other schools have been more cautious.

Schools skipping Skyline must defend their choice

One elementary school principal who left the district last year said she was asked to make a case that her school’s English language arts curriculum passed muster.

She and her teachers largely agreed the school would benefit from adopting Skyline in the later grades; after two years of pandemic schooling, educators felt drained and ready for a break from the labor-intensive process of designing lessons from scratch. But in the earlier grades, the principal compiled test scores and other data to argue that her teachers should be allowed to continue using their own lessons. The district agreed.

“They don’t come out and say, ‘You have to do it,’” the principal said. “But if you can’t prove your school is using a high-quality curriculum, then the pressure is on to adopt Skyline.”

Chalkbeat and WBEZ are not naming several school leaders who did not have district permission to speak with the media; the former principal asked to remain anonymous to avoid burning bridges with the district.

A high school principal said she asked most of her teachers to take last school year to “tinker” with Skyline and do the extensive professional development the district offers. But she has mandated it for a few teachers who did not have robust lesson plans and struggled in the classroom.

This year, the district asked schools to evaluate their curriculums across the board against a district rubric that defined what made for a quality curriculum and recently shared results with principals: Roughly 20% of campuses do not have quality curriculums in reading, math, or social studies, and about 10% do not have one in science.

Mary Beck, the district’s head of teaching and learning, said the district is now working with those campuses to make a plan.

“If you don’t have a high-quality curriculum, what’s your plan to get to a high-quality curriculum?” she said. “Skyline is obviously the example, but not the only example.”

The number of schools adopting Skyline is growing each year. As of January, as many as 432 schools were using the curriculum for at least one subject, roughly 83% of all district schools.

In elementary schools, the English curriculum is the most popular and math is the least (not including world languages, which are not offered by all campuses).

Majority Black schools have adopted the curriculum at the highest rates. Campuses that serve mostly white students — only about two dozen districtwide — have been slowest to embrace Skyline, Chalkbeat and WBEZ found.

In Chicago, 432 schools have adopted Skyline for at least one subject, with majority Black schools using the curriculum at the highest rates.

Skyline adoption has also been slower at high schools, though some high-needs South and West side campuses were early adopters across all subjects.

A couple of principals told Chalkbeat and WBEZ they opted in mostly just to get the free resources from the district.

The high school principal said her school adopted Skyline in all subjects, but buy-in varies.

On one end of the spectrum, science teachers at her school really like the curriculum, which draws heavily on the well-respected curriculum called Amplify Science, and have rolled it out faithfully.

On the other end, English teachers dabbled but ultimately returned mostly to lessons they had developed previously. Social science teachers found the materials too challenging for struggling readers; some are picking and choosing parts to incorporate.

Some teachers struggle to navigate Skyline

Caprice Phillips-Mitchell, the chair of the Chicago Teachers Union elementary steering committee and a kindergarten teacher at Fort Dearborn Elementary School on the South Side, said she hears from a number of teachers who are unhappy with Skyline. And this school year, she experienced some of the problems herself.

Phillips-Mitchell said parts of the Skyline curriculum are too challenging for students or require prior knowledge teachers need to fill in. Because online lessons and assignments are not “user friendly,” teachers say they are printing out the lessons and making copies. Sometimes when teachers try to go back to a lesson, it is gone and replaced with something new.

She said her school was told it must adopt Skyline. That meant she had to stop using an English language arts curriculum she and other teachers liked. Phillips-Mitchell says she believes schools serving low-income students of color are facing more pressure to adopt Skyline.

“Why give anyone a curriculum that’s not really ready to be rolled out?” she said. “Do you do it in some of these Black and brown communities that may not have such a voice?”

The Chicago Teachers Union applauds the district’s effort to create a curriculum bank. But chief of staff Jen Johnson said it is problematic that some teachers are being told that it’s mandatory, while district leaders insist it is not.

“The unevenness of implementation means that teachers are experiencing dramatically different messages,” she said. “We do not support this being some kind of citywide mandated curriculum that takes away important teacher autonomy.”

Johnson said staff need more planning time to consider and digest a new curriculum in order to buy into it and implement it well. She often hears about problems with the online interface or mistakes in the materials. For example, one social studies lesson somehow omitted an entire state.

Teachers and educators across the district interviewed by Chalkbeat and WBEZ echoed the concerns about the platform and what many said is an overwhelming amount of resources. The platform is designed by a company named SAFARI Montage.

The former elementary school principal said she understands the good intention of offering teachers a wealth of resources to choose from, but “Skyline is overly packed with lessons. It’s really too much information for teachers.”

A couple of educators told Chalkbeat and WBEZ that because the Skyline platform was frustrating to use, they instead accessed math materials directly on the website for Illustrative Math, the curriculum that the district adapted for Skyline — essentially defeating the purpose of having a district math curriculum.

A current West Side elementary principal said his teachers largely moved away from using the Skyline reading curriculum in the early grades — with his blessing — because of some of these frustrations. His school sprang for a different early literacy curriculum this year.

Other educators say some of the materials for students have dense text and few engaging visuals. Much of the curriculum is translated into Spanish, but there are questions about how well-suited the lessons are for English language learners. And some teachers say it can be too challenging to make the lessons accessible for students reading below grade level, especially at the high school level.

Bronzeville Classical Principal Nicole Spicer believes that Skyline has made her teachers’ jobs easier and made lessons more engaging for students.

At Bronzeville Classical, teachers and Spicer, the principal, say they can relate to some of these concerns. But they also feel strongly the district has been listening and making helpful changes — and overall, Skyline has enriched their teaching and made their work easier.

Earlier this winter, sixth graders in Hernandez’s classroom learned about how rugged mountain geography influenced the early engineering of the ancient Inca people. She took the Skyline lesson on the topic and made it her own, creating engaging slides with stunning images of the Andes mountains.

Skyline, Hernandez says, has helped her cut down significantly on the time she used to spend on nights and weekends looking for lesson materials online.

Later, students explored design and engineering by the Spartans and ancient Greeks — culminating in a discussion of how these long-gone cultures influence design in present-day Chicago, such as its Soldier Field.

“They’re able to make that connection with the past and the present, which is really neat,” Hernandez said.

Javee Hernandez’s adoption of Skyline has saved her time on curriculum development over nights and weekends.

Beck, the teaching and learning head, says the digital curriculum was designed to be revised and improved quickly in response to teacher and student feedback. District leaders meet regularly with a steering committee of 120 teachers to get ongoing feedback. Beck said the district worked with SAFARI Montage to improve the platform and revamped some courses and units. It’s now focusing on upgrading materials meant for students.

Isabella Kelly, a member of a districtwide student advisory group, said fellow students had both positive feedback and suggestions for improving Skyline during a focus group on the science and French curriculums she hosted last spring.

Kelly, an Ogden High senior and student leader with the group Mikva Challenge, said students found the lessons engaging and loved the opportunities to collaborate on projects and work in small groups. But they also sometimes struggled navigating the online platform.

“The biggest challenge they faced was learning along with their teachers,” she said. “They wanted a little more assistance.”

Skyline is a key tool for academic recovery, district leaders say

In a recent webinar, district leaders reminded principals that rolling out a new curriculum is a heavy, time-consuming lift, and urged them not to get discouraged by the “growing pains,” as Chief Education Officer Bogdana Chkoumbova put it.

By keeping lessons and assignments squarely on grade levels, the curriculum can play a key part in COVID academic recovery, officials have said. It’s encouraging teachers to avoid constantly reteaching material from earlier grades — an approach shown to hamper academic catchup. That’s challenging work, Beck acknowledged, but the schools can layer other support, such as a specialized program for struggling readers called Wilson.

Beck said Chicago has worked with a group of curriculum experts to continually evaluate Skyline and better understand its impact on student outcomes, but that’s still a work in progress. The University of Chicago is studying whether the curriculum is paying off in early literacy improvements.

Steiner, at Johns Hopkins, says he is generally skeptical of the enormous energy and expense that go into creating an in-house curriculum in all subjects given the quality of off-the-shelf curriculums — especially if the district makes it voluntary. But he said rallying around a strong curriculum, particularly the collaborative work of teachers adopting it as grade level or subject matter teams, can be powerful for urban districts such as Chicago.

Some educators say that in a district where top leadership has been in flux for years and initiatives come and go, they are reluctant to buy into Skyline in a big way.

But Chkoumbova said the district knows adoption is a “long and hard process for schools,” and Skyline is here to stay.

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at [email protected].

Sarah Karp covers education for WBEZ. Follow her on Twitter @WBEZeducation and @sskedreporter.

[ad_2]

Source link

Meet Our Successful Graduates: Learn how our courses have propelled graduates into rewarding

careers. Explore their success stories here!

Discover More About Your Future: Interested in advancing your teaching career? Explore our

IPGCE, MA, and QTS courses today!

Explore Our Courses: Ready to take the next

step in your education journey? View our

comprehensive course offerings now!