[ad_1]

Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Education notified DeVry University that it plans to recoup more than $23 million from the institution to claw back money spent on federal loan discharges for some of its former students.

Around 650 students who previously attended the for-profit university filed claims against the institution under the borrower defense to repayment regulation, which allows students to have their loans discharged if their institutions defrauded them. The rules also let the Education Department recoup these costs from colleges.

DeVry sued the Education Department shortly afterward. The university argued that the agency’s attempt to recoup funds is unlawful because the department adjudicated the applications as a single group rather than looking at the individual details of each case.

DeVry isn’t likely to be the last one to take this argument to court.

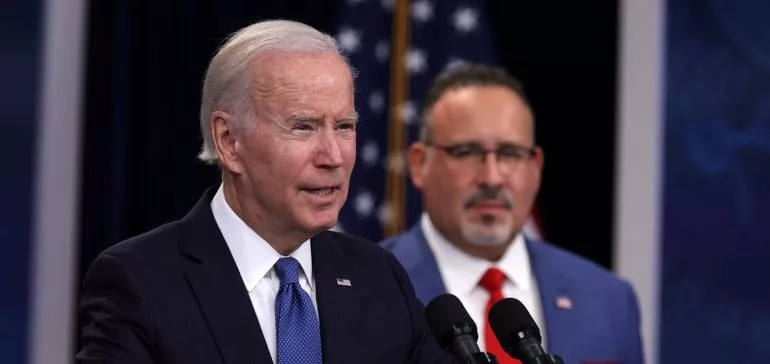

That’s because the Biden administration has finalized new regulations going into effect next year that will make it easier for the Education Department to discharge debt for large groups of students misled by their colleges, instead of conducting individualized reviews of student claims.

Some higher education experts consider these new regulations legally vulnerable, while others argue the Education Department’s proposals are squarely in line with the law. Either way, the new borrower defense regulations will likely be a lightning rod for legal battles.

Is individual review possible?

The borrower defense rules have undergone massive change in the past decade. The once little-known regulations rose to prominence after the sudden closure of for-profit chain Corinthian Colleges in 2015 left thousands of students saddled with debt and no degrees to show for it.

Since then, each presidential administration has proposed its own version of borrower defense rules, creating a confusing web of regulations for the Education Department, colleges and students to navigate. The newest regulations, which take effect in July, restore the Education Department’s ability to consider claims as a group rather than reviewing individual applications. The Trump administration had barred group borrower defense claims in its version of the rules.

The department can either form a group itself, or it can choose to create one based on requests from state attorneys general or nonprofit legal assistance organizations. Borrowers may have their loans discharged if their colleges made substantial misrepresentations, breached contracts, used aggressive and deceptive recruiting, or engaged in other fraudulent activity.

Group discharges are an important way for borrowers to receive relief because many of them don’t know about the borrower defense process, said Kyle Southern, an associate vice president for higher education quality at The Institute for College Access & Success, a student research and advocacy organization.

“By having this kind of group process, we can make all the borrowers whole who are entitled to the relief under federal law, without putting the burden on each individual defrauded borrower to pursue an individual BD claim,” Southern said. “As we’ve seen over recent years, those claims can wait for years and years.”

A backlog of borrower defense claims has reached staggering numbers. As of November, the Education Department had about 443,000 pending applications, yet only 33 employees were working to adjudicate those claims, according to court documents.

Many of them may soon receive relief — the agency recently agreed to settle a lawsuit brought on behalf of borrowers, Sweet v. Cardona, by automatically clearing $6 billion worth of student loans for roughly 200,000 borrowers who filed claims. The borrowers who brought the lawsuit alleged the Education Department had delayed deciding their cases.

Students who filed a borrower defense claim and attended one of the schools on a list of 150-plus colleges will automatically have their debts cleared. The department will streamline review of students who attended colleges that aren’t on the list but have a pending claim.

In the settlement approval, a federal judge calculated how long it would have taken department employees to review the existing borrower defense claims individually.

“If, hypothetically, the Department’s Borrower Defense Unit had all 33 of its claim adjudicators working 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year (no holidays or vacation), with each claim adjudicator processing two claims per day, it would take the Department more than twenty-five years to get through the backlog,” the judge wrote.

The Education Department said it would use a separate legal authority from the borrower defense regulations to clear student debts under the settlement.

But the agency may end up leaning on group discharges to resolve claims if the backlog continues. While the $6 billion settlement could provide relief for more than 200,000 borrowers — making a serious dent in pending claims — it could become tied up in court if it is appealed. Moreover, large swaths of students not covered by the settlement could soon come forward alleging their schools defrauded them.

Kyra Taylor, staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, an advocacy group, said there are many more students who are likely eligible for borrower defense relief, but few of them know about their right to receive loan discharges.

“There’s a lot of reasons for the department to continue using its group discharge authority — both because it’s more efficient to do it in a group way instead of going one by one by one as people become aware of their rights, but also because it’s the right thing to do,” Taylor said.

Legal trouble looms

For-profits have been vehemently opposed to the new regulations. Career Education Colleges and Universities, which represents for-profit colleges, slammed the final rule when it was released, arguing it has serious regulatory flaws and deprives colleges of due process rights.

The organization continues to oppose the regulations.

Nicholas Kent, chief policy officer at CECU, said the Education Department is expected to handle borrower defense claims largely though the group process moving forward. Congress didn’t authorize the department to create a borrower defense program to decide on thousands of claims at once, Kent argued.

“The department has created this monster,” Kent said. “That’s not what the borrower defense authority was initially intended for.”

CECU and others take issue with the regulation’s provision that will allow state attorneys general and legal assistance organizations to ask the department to form borrower defense groups.

“The department is abdicating responsibility to state and to private legal assistance organizations to do the work that Congress envisioned the department to do,” Kent said.

Some practicing lawyers agree.

The ability for the department to create borrower defense groups this way oversteps what the statutory language intended, said Aaron Lacey, who chairs the law firm Thompson Coburn’s higher education practice. That could create an opening for the rules to be challenged in court, he said.

It remains to be seen whether a college would have the legal standing to sue the Education Department if its former students received debt relief through group discharges. The department’s new rules separate loan discharges from the recoupment process, allowing the agency to forgive debts without first going after colleges to cover the costs.

Lacey argued that schools would be able to demonstrate that their reputations have been damaged if their students received debt relief.

Similar arguments were raised against the $6 billion settlement. Four institutions on the Education Department’s list of colleges whose former students would receive automatic relief said their inclusion damaged their reputations — even though the agency said the list wasn’t a formal finding of misconduct.

But Taylor, of the National Consumer Law Center, disagreed with Lacey’s view.

“Schools have to be injured in a legally cognizable way to bring a lawsuit, and they wouldn’t be injured just because some students got their debts discharged,” Taylor said. “It’s the government that’s choosing to cancel that debt.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Meet Our Successful Graduates: Learn how our courses have propelled graduates into rewarding

careers. Explore their success stories here!

Discover More About Your Future: Interested in advancing your teaching career? Explore our

IPGCE, MA, and QTS courses today!

Explore Our Courses: Ready to take the next

step in your education journey? View our

comprehensive course offerings now!